Esmé Goodson shares with us an article based on the research she conducted as part of her undergraduate dissertation, in which she looked at the use of figurines as grave goods in Romano-British burials with the aim of understanding why they were present in the burials of certain demographic groups.

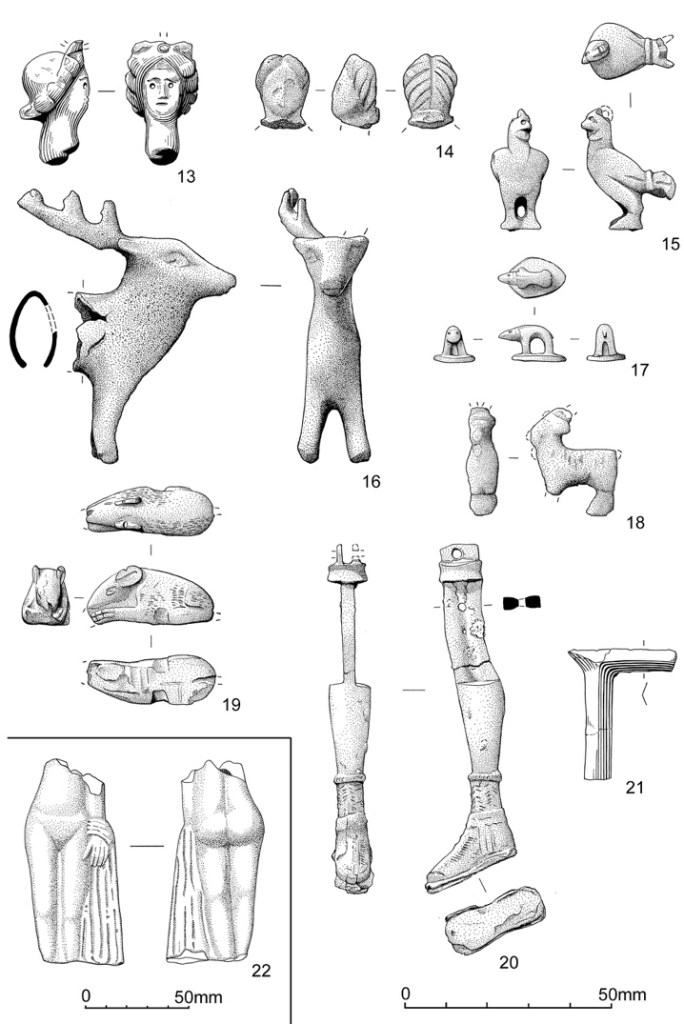

Grave goods were objects buried with the dead. In Roman Britain, these could include (but were not limited to) weapons, pottery and jewellery. In this case, our focus will be on figurines, although these were not common Romano-British grave goods. Figurines were small, portable objects, often shaped like humans or animals. They had many uses in Roman Britain: as well as grave goods, they could function as religious offerings, for example. Several materials were used to make figurines, though the ones most common among figurine grave goods were pipeclay (a fine, white clay – so called because a similar type of clay was used for medieval pipes), metal (often bronze) and jet. Pipeclay figurines were imported from Roman Gaul and, while some metal figurines were imported, others were made in Britain. Jet, meanwhile, was a localised material, so these figurines were likely crafted in Britain. An amber figurine and an ivory figurine have also been found as grave goods – though materials such as these are uncommon.

So, who were these figurines buried with? Figurines were mostly buried with infants (less than one year old) and children (one- to thirteen-year-olds), as well as young women (females under around twenty-five). The inclusion of figurines with infants is particularly interesting given that infants in Roman Britain were often buried with few, if any, grave goods, in buildings within a settlement rather than in cemeteries outside a settlement. Notably, figurines do not appear to have been used as grave goods for men.

To understand why figurines appear to have been associated with specific demographics, it is worth considering what kind of objects these were. Several academics have suggested that figurines could have been toys – a proposal which seems appealing given their association with child burials. However, we must be speculative of such an interpretation. Our understanding of what constitutes a ‘toy’ is shaped by our experience in the modern world, which does not necessarily match ancient realities. While children might have played with figurines, we cannot determine this simply from their proximity in burials.

Looking at where these figurines were found can give us a better understanding of the circumstances they may have been used in. Aside from in funerary contexts, figurines were mostly found in domestic and ritual contexts (locations such as homes, temples, wells etc.). This suggests that figurines were perhaps household objects, as well as suitable religious offerings. In fact, some academics have even suggested that figurines were used in household shrines.

The ritual nature of figurines may be reinforced by the identification of these figurines with deities. However, we ought to be careful when suggesting such identifications. Academics have often identified figurines with Graeco-Roman deities such as Venus. But while similarities between pipeclay ‘Venus’ figurines and statues of the same goddess indicate that she was the deity in mind when these figurines were made, there is no way of determining whether local British people thought of these as Venus figurines or whether they associated them with some local deity – or perhaps even a generic depiction of a woman. Nevertheless, the modelling of some figurines on deities when manufactured suggests that these were intended to be religious objects, regardless of how they were used in reality.

In terms of the choice of figurines used as grave goods, the most common figurine forms in Britain (the pipeclay Venus and pipeclay Dea Nutrix) appear frequently in burials. Scholars have suggested that these forms were suitable for the burials of juveniles because of their associations with fertility and protection. Because these forms were abundant, we cannot exclude the possibility that they were merely selected because they were the most readily available.

However, some less common figurine forms also appear frequently in burials, such as pipeclay busts of women and children. Since young women and children were the most common age groups found buried with these figurines, these busts indicate a conscious concern with the identity of the deceased being commemorated. This evidence suggests that the choice to bury young women and children with figurine grave goods was an intentional one.

In some cases, the choice of materials may have been particularly significant. Several individuals were buried with jet figurines, most of which took the form of bears. Jet has electrostatic properties: it emits a small electric charge when rubbed (amber has these same properties). Some jet figurines show signs of rubbing, such as a jet lion from a burial in Chelmsford, demonstrating that people were aware of these properties.

Other common figurine materials had value to them too. Metal, for instance, was inherently valuable, while pipeclay imports from Gaul were uncommon. The value and properties of the materials used to make figurines would likely have made them high-status objects.

So, in short, figurines were high-status objects, with domestic and religious associations, and they appear to have been consciously selected for commemorating specific identities. But why were they suitable for commemorating certain demographics?

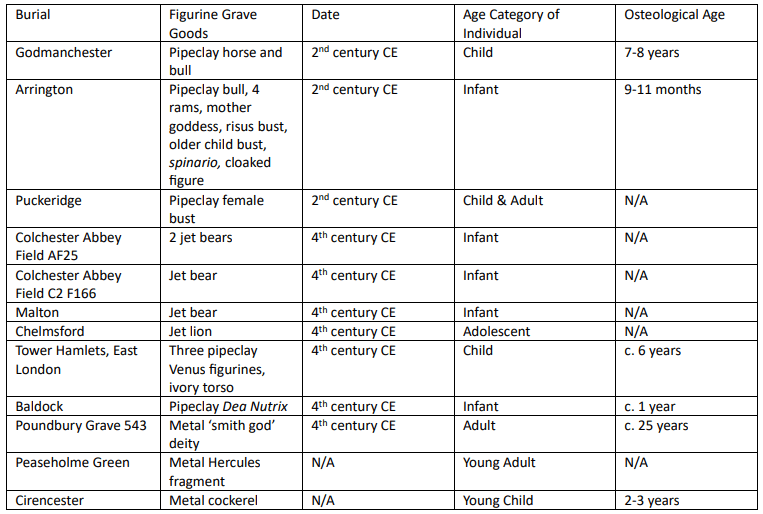

A useful concept for understanding this is the ‘life course’. This is the idea that one’s life is made up from different stages. In the present day, we think of age in terms of different life stages: we go from being a baby to a toddler to a child to a teenager and so on. The Romans certainly had their own way of understanding the life course. Horace’s Ars Poetica describes a male life course, relating the characteristics of a young boy, youth, man and elderly man in turn. Such a text demonstrates awareness of the life course in the Roman world. A closer look at burials with figurine grave goods, where the ages of the deceased have been determined through osteology, shows that figurines were most often used as grave goods for what we would call ‘infants’, or younger children in general, and ‘young women’. By situating these identities within their broader life course, we can better understand why figurines may have been suitable grave goods.

To start, Pliny the Elder in his Natural History claims that infants were not considered human until teething. The distinction of infants from other Roman age groups can also be observed archaeologically, suggesting that this was seen as a separate life stage. As mentioned, infants were often buried inside buildings within a settlement. Meanwhile, children and adults were usually buried outside the settlement in cemeteries. This highlights how infants were perceived differently from older humans in Romano-British society. Therefore, within the life course, the ‘infant’ stage came before a major life transition: becoming a child – or, according to Pliny, becoming human.

The six-year-old from the Tower Hamlets cemetery in London could have been considered part of this demographic. This child sadly suffered from malnutrition and rickets during their lifetime, making them smaller than a normal six-year-old. Therefore, they could have been perceived as biologically younger, perhaps influencing their funerary commemoration.

Furthermore, evidence suggests that a ‘young woman’ life stage preceded a major transition in the life course: marriage. Tombstone commemorations for women in the west of the Roman Empire suggest that the average age for a woman to marry in this region was in her late teens or early twenties. The ‘young women’ buried with figurines tend to be part of this age group, or younger.

Young women were also commonly commemorated with bountiful grave goods, such as jewellery. This distinguishes this demographic from older women, whilst also emphasising a desire to commemorate this group extravagantly.

The burial of a young girl from Godmanchester, too old to be considered an infant, may have been viewed as a young woman – an idea reinforced by the child-sized bangles buried with her. This evidence indicates that Roman social identities did not always align neatly with modern ones.

When infants and young women died before a major life transition, they died ‘before their time’. Their deaths may therefore have carried a greater sense of loss. As I have established, figurines were valuable and tactile. This gave them power, something only reinforced by their religious associations. Because of this, they may have been useful for negotiating grief. Moreover, infants and young women would have been perceived as domestic identities: both would have been dependent on their families and households. As I have mentioned, figurines had strong domestic associations. They were likely domestic objects and thus suitable for commemorating domestic social identities. This explains why figurine grave goods were suitable for commemorating young women and juveniles but not adult men. In the Roman world, men engaged predominantly in the public social arena, making this form of funerary commemoration potentially unsuitable for them as a demographic.

So, it seems that figurines functioned as powerful commemorative objects in response to grief. This is particularly significant for our understanding of infant burials. As mentioned, infants were typically buried without grave goods and inside buildings, which has led some academics to claim that infants were disposed of unceremoniously or were not cared for. Nevertheless, the presence of figurine grave goods with infants indicates that they were loved and grieved for. This encourages us to question these previous interpretations of other infant burials. Perhaps we should entertain the possibility that infant burials within functional buildings allowed their living loved ones to remain close to them. At the very least, we should perhaps start regarding this practice as simply a different form of funerary commemoration, rather than as something inherently negative.

There is also the element of tradition to keep in mind. In other locations in the Roman Empire, such as Africa, children were buried with figurines. Moreover, in earlier periods in Greece, figurines were used as grave goods for children (in Corfu, for example). This was, therefore, not a tradition exclusive to Roman Britain, or even the Roman period. The legacy of this practice reinforces the fact that figurines were suitable objects for commemorating untimely deaths. Perhaps the very factors which motivated the use of figurines as grave goods for these social identities in Roman Britain also influenced the use of figurine grave goods in other regions and at other times.

Images:

A selection of pipeclay figurines from the burial of an infant from Arrington, Cambridgeshire. (2nd century CE) © Esmé Goodson

A table with data for the osteologically aged burials with figurine grave goods (Data from Crummy 2010, Durham 2012, Fittock 2017, Cotswold Archaeology 2019) © Esmé Goodson

Figure bronzes and pipeclay Venus figurine from Elms Farm – This Photo by Unknown Author is licensed under CC BY

Roman copy of the famous ‘Knidian Aphrodite’ by Praxiteles (fourth century BCE). This sculpture was the first nude depiction

of the goddess and inspired later depictions of her in antiquity.

You must be logged in to post a comment.